Q&A: GE executive looks ahead

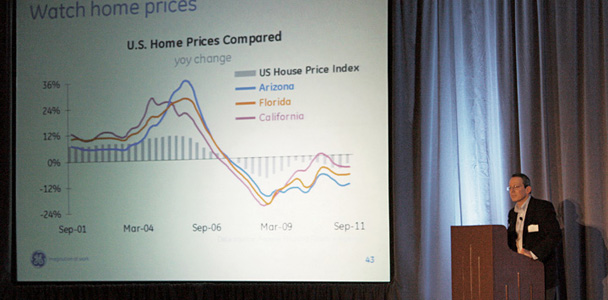

Kicking off the 2012 Miami International Boat Show, the GE Capital & NMMA Industry Leadership Conference featured an economic outlook by Rob Podorefsky, managing director of GE Capital Interest Rate Management Group.

Podorefsky detailed what is ahead for the economy and what to watch for in 2012, examining the effects of the historically low risk-free interest rates imposed by the Federal Reserve and the impending tax climate change. Following his enlightening presentation, he took questions from a few of the hundreds of marine professionals in the crowd. The following are his answers.

Where are we in the business cycle?

Podorefsky: We typically don’t have recessions in America from a business cycle perspective without having huge amounts of overhang – previously produced inventory that you can’t sell requiring production cutbacks. A downturn at this stage would be more likely from a shock, which can be unforeseen. Inventory is being well-managed at the business level. So, we are not due for an inventory-led downturn; we are gradually building momentum and actually going in the opposite direction.

What impact does being in an election year have on investing?

Podorefsky: We had a pickup in investment in 2010 and 2011 assisted by accelerated depreciation. We don’t have enough 2012 data yet for the investment category, but it is likely to be more challenging, given that accelerated depreciation is behind us. I think one of the shortcomings by the current administration over the last couple of years was a lack of cheerleading. There were favorable data points, many favorable trends, and several developments separating us from the worst of the recession that could have been called out along the way. Opportunities were missed, and it is puzzling. But in an election year, you are likely going to see more cheerleading, and I think it is going to resonate. There should be more positive tailwinds on the back of political posturing than headwinds.

How do the historic low interest rates at the risk-free federal level translate to the costs of our credit?

How do the historic low interest rates at the risk-free federal level translate to the costs of our credit?

Podorefsky: The tie-in is not direct because your capital providers are not the federal government. They are financial institutions that have their own funding realities. And there are more differences between the funding of your capital providers today and the federal government than there have been historically. You are witnessing [risk-free rates] that are artificially low due to the Federal Reserve’s extraordinary accommodation, and additional global capital flows into U.S. government debt due to Europe’s sovereign debt crisis and geopolitical uncertainty.

What happens if those risk-free rates suddenly increase to more normal levels?

Podorefsky: If risk-free rates go up even 300 basis points, what will that do to the overall economy? It is almost like large spikes in gasoline prices — it is the pace of the increase to be most concerned about. If interest rates rise rapidly, you might have a dislocation that could be destabilizing to the broader marketplace, which could lead to problems in the equity market. That could become a meaningful economic headwind.

On the other hand, if a gradual upward rate adjustment was to unfold, it would likely be viewed as favorable, indicating fewer global concerns and more focus on improving trends, which are good things. And if that happens because the Federal Reserve has gotten out of the way, we will hopefully see some market discovery again for Treasury yields, which has been limited recently given the Fed’s bond buying programs. On this point, historically low government borrowing costs have removed an incentive for Washington to tackle the budget mess. The near $460 billion spent in the federal budget last year on interest expense on our public debt would probably exceed $1 trillion [with more normalized interest rates]. With that enormous expenditure, you would unlikely have as much budget conflict in Washington because the need for fiscal solutions would be even more pressing.

What will happen to tax rates for the individual going forward?

Podorefsky: Nothing likely happens this year, but 2013, after the election, is a different matter. It is not clear if you get tax changes like the Buffett rule passed or if they eliminate the alternative minimum tax. But we should realize that the government needs revenues and they are not going to give up on trying. The Bush-era tax cut extension ends Dec. 31, and there is approximately $4 trillion there. But there are a lot of options outside of tax increases, outside of the Bush tax cut extension that can go very far here.

With taxes possibly going up, what affect will that have on buying habits?

Podorefsky: There will be less disposable income, no question. But we have had episodes in the past where tax increases have gone throughout the system, and the wealthy were more affected than the middle class. There typically is a period of adjustment, which is about two quarters. The legacy of the change is longer than you think. People are not happy about it, and then they eventually adjust. The potential for tax increases are so pre-advertised in a way right now that by the time 2013 rolls around there may be less of an effect. And if the economy is still not in a good place next year, there will be political pressure to extend those Bush-era tax cuts.